The country of reinforced concrete mushrooms

initially published in RZUT magazine,

07/2023, Warsaw

07/2023, Warsaw

bunker- ‘a hardened shelter, often buried partly or entirely underground, designed to protect people, military equipment and resources from bombardment or other types of attack’ 1

According to the definition, the primary purpose of a bunker’s construction is defence. In the case of Albanian shelters built during the Cold War, this intention was never properly executed. At a time when the world was developing anti-nuclear defence systems, Albania pursued a bunkerisation programme. Projekti Bunkerizimit was a spatial and political self-defence plan launched by Enver Hoxha in the 1970s. The project aimed to build 750,000 bunkers across the country to provide shelter for all soldiers and civilians from military enemies. However, none of the potential aggressors ultimately attacked, leaving Albania with almost mythical amounts of concrete mushrooms. The bunker became the core, the symbol of Hoxha’s political regime, driven by his personal views and trauma. The widespread fear, rooted in the constant invasions and years of occupation of the country, had no objective basis concerning the reality of the 1970s. However, the material remains, in the form of countless bunkers, keep the spirit of the past still present in Albania.

1. Bunkers scattered in mountainous areas, Albania 2010, photo by Jeanie Mackinder

bunker - an architectural object derived from military typology

In 1944, after years of occupation by the Italian and German armies, a new period in Albanian history began. At this time, Enver Hoxha, the First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Labour Party and political commissar of the National Liberation Army, was the only candidate elected Prime Minister, and the country was declared a People's Republic.

Throughout his dictatorship, Hoxha broke off diplomatic alliances, gradually separating Albania from the international environment and eventually completely isolating the country. Therefore, the capability of self-defence became the dictator's priority, and the plan with the slogan ‘bunker for every family’ was the leading government programme. The constructed political narrative assigned Hoxha the role of protector, whereas the state offered the Albanians a panacea, formed in an architectural object, a materialised idea of security - a bunker.

2. ‘In Your Vein’, paining by Enkelejd Zonja

Hoxha depicted as the resurrected Jesus who allows the unbelieving Thomas to put his finger in his wound.

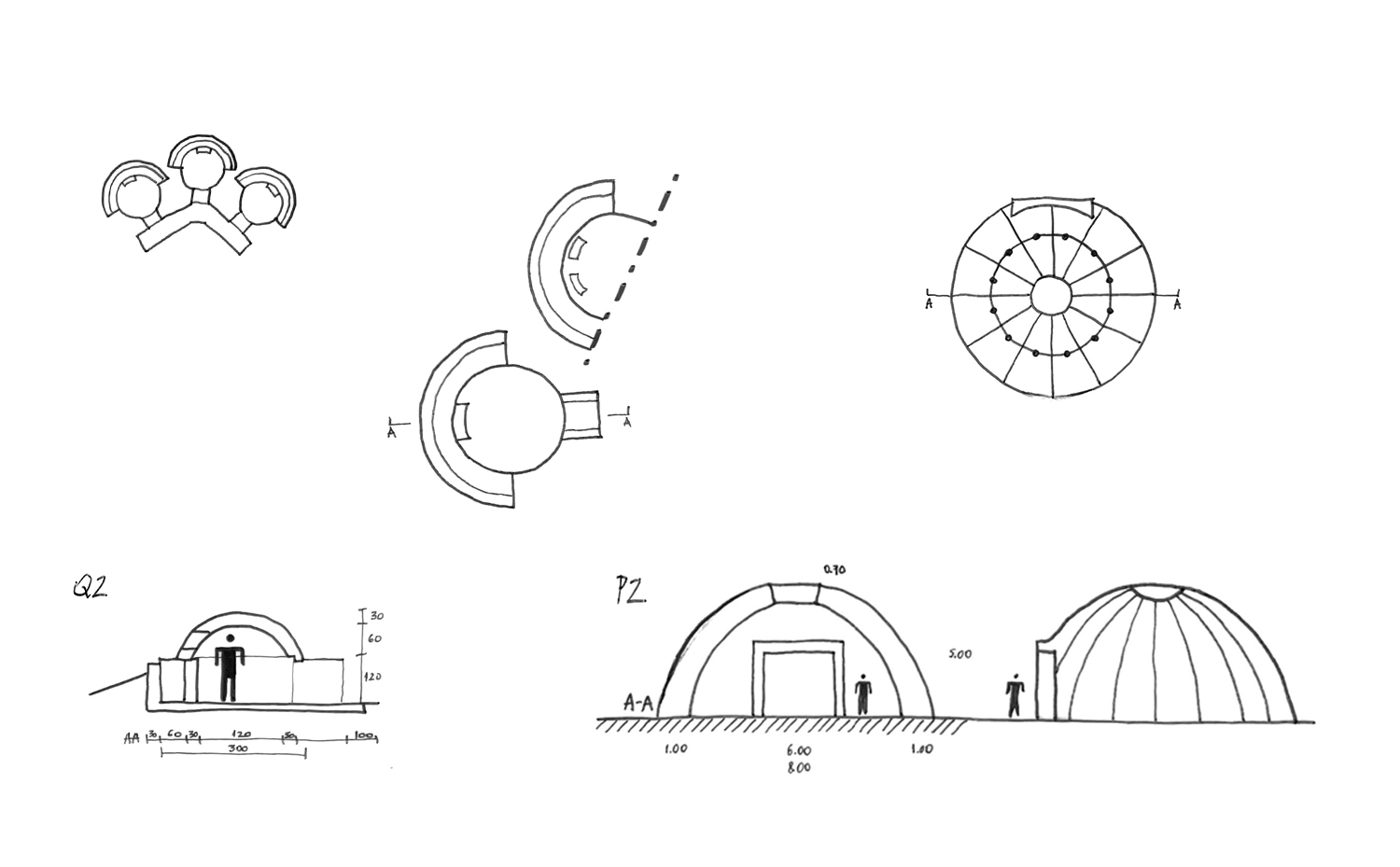

The concrete mushrooms were designed in three sizes. The smallest and most common type was the QZ (Qender Zjarri) bunkers, designed for a single soldier and his weapons. Along the coastline, QZ bunkers were often located in groups of three and connected by concrete corridors. These simple structures did not fully comply with the rules of military defence, according to which soldiers fighting at the front should never be scattered individually. The medium-sized bunkers, PZ (Pike Zjarri), considered this aspect. They were designed for groups (some even for more than ten people) or small artillery. The structural elements of PZ shelters were prefabricated and assembled on-site.

The last and most solid of the Albanian bunker types were the Special Structures (Structure Speciale). Built only for important political figures and their families or as bases for submarines, heavy artillery and aircraft. Of all three types of bunkers, only these were equipped with anti-nuclear tunnels, necessary in the event of a possible nuclear attack. Thus, absolute security was provided only to significant political individuals, while the illusion of it was offered to the rest of the nation.

3. Sketches of the construction diagram of three types of bunker size.

The Albanians' generational trauma, caused by the centuries of invasions and occupation by the ancient Greeks, Romans and Turks, among others, provided the new communist state with arguments that reinforced Hoxha's status and built his image as 'father and protector’ of the country. The plan to create a line of defence against the occupying forces fuelled a sense of fear and created, at the same time, a seeming vision of security.

As a response to illusory reality, Albanian bunkers can be perceived as heterotopias. Places whose ‘(...) role is to create a space of illusion that exposes any real space, (...) or, on the contrary, their role is to create another real space (...)’. 2 Projekti Bunkerizimit is an example of a form performing a function not as a definite material space but rather as a psychological and symbolic one. The semi-spherical structure of the bunker was a spatial response to Hoxha's paranoid fears, intended to offer the illusion of protection and autonomy from lost allies.

Regardless of the questionable practicality of these constructions and the lack of relevance to the political situation, Hoxha's paranoid plan had to be fully realised. Rather than military tactics and rational thinking, the drive to meet quantitative targets (a planned 750,000 structures) became the motivation for introducing prefabrication technology. This mass production raised doubts not only about the validity of the scale of the premise but also about the quality of the completed bunkers. The concrete structures were primarily intended as shelters, so their quality should have been a priority. At the same time, the materials and methods used in their construction did not meet basic military requirements. ‘For us, as part of the army, it was shameful to see that these structures did not have defensive capabilities,’ said Rrahman Parllaku and Edip Ohri, Albanian soldiers who fought during the Second World War and the Kosovo War.

It is estimated that, due to the mass production of bunkers, the Albanian landscape gained from 100,000, even up to a planned number of 750,000 reinforced concrete mushrooms. The numbers are impossible to determine today, as all maps and documents were lost after the fall of communism. Hoxha's concrete mega-investment plunged the country's already unstable economy. The construction of the bunkers consumed almost 2% of GDP annually, and the cost of building one structure was compared to the cost of building a small apartment. The entire budget of the country and all available building materials were spent on spreading illusory security, which was, in fact, a representation of the military regime in public space.

However, the hardship of daily life under dramatic economic conditions was not the only consequence of the bunkerisation plan for Albanians.

BUNKIER - a symbol of the past, a particular type of Albanian monument

Living in a militarised landscape and surrounded by defence structures generated a constant state of tension and anxiety about the country's future. The programme intensified the sense of social anxiety rather than easing it. ‘(...) it is challenging to decondition our minds, our feelings: these are the effects of post-totalitarian trauma in our society’. 4 Till that day, bunkers are a tangible aspect of a complicated past that cannot be easily forgotten. In a country with a relatively short period of autonomy, bunkers have been elevated to the status of an architectural symbol. They have even been referred to by some as our cathedrals5 demonstrating how important it is for a society to have its symbols of worship. In 1999, when Albania found itself in the zone of Serbia's conflict with Kosovo, it was the first time that bunkers located along the border were used for their intended purpose. And that was when the myth of nuclear defence, or any resilience of these facilities, collapsed—the bunkers just fell apart.

Bunkers - a permanent feature of Albania's landscape

Bunkers have transformed from a symbol of oppression into an element of everyday life. As an integral part of familiar surroundings, they are no longer judged by practicality or usefulness. The entire landscape has been subordinated to bunkerisation, creating a new layer of Albania's topography. Projecti Bunkerizimit has not only taken root on the strategic military front lines. A country with a highly diverse and one of the most virginal landscapes in Europe, in the 1970s, was enriched with an additional element—concrete mushrooms. Bunkers are scattered across urban, rural, coastal and mountainous areas. ‘Hoxha and his party managed to transform all forms of material culture for their purposes, including (...) the entire landscape.’6

4. 'Triple series' of connected QZ bunkers on the beach, Albania 2009, photo by Elian Stefa and Gyler Mydyti

After years of being unused, overgrown and blended into their surroundings, bunkers are still easily recognisable by their artificially symmetrical shape. Despite their closed form, they allow different organisms to penetrate their interiors, overgrow and function within them. Resembling their surrounding environment, bunkers have taken on the role of rock formations, coastal shorelines, and forest undergrowth. Sometimes, they function as backyard larders or even restaurants. Adopted by the Albanian landscape and society, bunkers are an integral part of today's environment. They are objects between a man-made structure and a structure created by nature. They belong to both while at the same time not being fully taken over by either.

Through their ubiquity, the bunkers have gradually become unnoticeable to the Albanian population. This invisibility can be seen as a particular in-between state. The fact that bunkers have never had to fulfil their functional purpose positions them on the margins of utility. They are in a liminal state. ‘Liminal entities are neither here nor there; they are between the positions assigned by law, custom, convention and ceremonial’.7 The actual fulfilment of the role of the bunkers, however, would have meant a state of war and a national tragedy for Albanians.

In reality, the dictator's speculation positioned bunkers on the periphery of everyday life. Aware of the unrealistic and non-functional character of the programme, Hoxha carried out his life plan as an act of spatial performance on a national scale. Its protagonist, the bunker, has evolved from a foreground character of the plan to the role of a citizen, a neighbour. |

5. Bunkers in the city of Durres, site visit, Albania 2023, photo by Anna Halek

*[orgignally written in Polish, translated by the author]

References:

- G. Mydyti and E. Stefa, Concrete Mushrooms. Reusing Albania's 750,000 Abandoned Bunkers, Barcelona 2012, p. 30

- M. Foucault and J. Miskowiec, Of Other Spaces, "Diacritics" The Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore 1986, p. 27

- G. Mydyti and E. Stefa, dz. cyt., p. 26

- G. Mydyti and E. Stefa, dz. cyt.,ps. 34

- O. Rupeta, Temples of an Atheist State, BROAD Magazine, red. Gergo Farkas, 2018, online publication, https://www.broad.community/blog/2018/6/8/temples-of-an-atheist-state-oleksandr-rupeta, dostęp 24/02/2023

- M.L. Galaty, S.R. Stocker, Ch. Watkinson, The Snake That Bites. The Albanian Experience of Collective Trauma as Reflected in an Evolving Landscape, "The trauma controversy: philosophical and interdisciplinary dialogues", Nowy Jork, 2009, no 9, p. 172

- V. Turner, Liminality and Communitas, "The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure", Chicago 1969, p. 359

Pictures:

- available under open access with commercial use

license: Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 G eneric

source: Wikimedia commons, Flickr

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Four_bunkers_in_Alban - available under open access with commercial use

license: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Un ported

source: Wikimedia commons, Concrete Mushrooms P roject

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Albania_triple_bunk - available under open access with commercial use yjjic

license: Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Un ported

source: Wikimedia commons

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bunkers-in-Durrr