Construction sites as spaces of discourse:

By building, we crate.

initially published in the newsletter of Kollektiv Kaorle,

07/2024, Vienna

Passing the fences of urban construction sites, the mystery builds up. Often enclosed for safety measures, building sites remain inaccessible for those outside the triangular hierarchy- architects, investors and construction companies. With more significant projects, the mystery of what happens behind the fence is mimicked by colourful renders with cheerful people placed around newly built or renovated spaces. While some people try to peek through the gaps between the fence spans, others jump up or bend over the covers, the most pass by impassively.

A construction site is defined as “an area of land where something is being built” 1 and is possibly described by several other characteristics, such as the involvement of different professionals like architects, engineers, construction managers, and labourers. It can, therefore, be said that the construction site is a place of human interaction, a temporarily demarcated space within which relationships are formed. In particular, relationships between industry professionals.

In this way, the construction site was to be seen as a place for creating and enhancing neighbourhood interactions and social responsibility. Self-build projects can serve as platforms for raising awareness and a sense of belonging, as well as building and forming social bonds. This perspective allows for a deeper understanding of the social dynamics and collaborative processes forming at construction sites.

A great example of such an attempt occurred in the 1980s in London. Walter’s Way and Segal Close are two settlements based on a self-build housing scheme. The concept for this initiative was born out of the architectural reflections and personal developments of Berlin-born architect Walter Segal. From the beginning of his career, Segal was concerned with questions about ‘empowerment, collaboration, and democratic design’. With these thoughts in mind, he delved into architecture until he sparked the self-build revolution.

The actual translation of his ideas into physical matter occurred in 1963. During the construction of his own house, Segal erected a temporary structure for his family to live in. All the methods used in that project eventually became the main principles of Walter’s Way and Segal Close. The house was based on a modular system, with easily accessible building components, and took just two weeks to build. In the 1970s, London was grappling with a housing crisis, and the city’s council embraced Segal’s Method openly and enthusiastically. Eventually, the concept of the main structure was simplified so that people without professional experience could build their own houses.

![]()

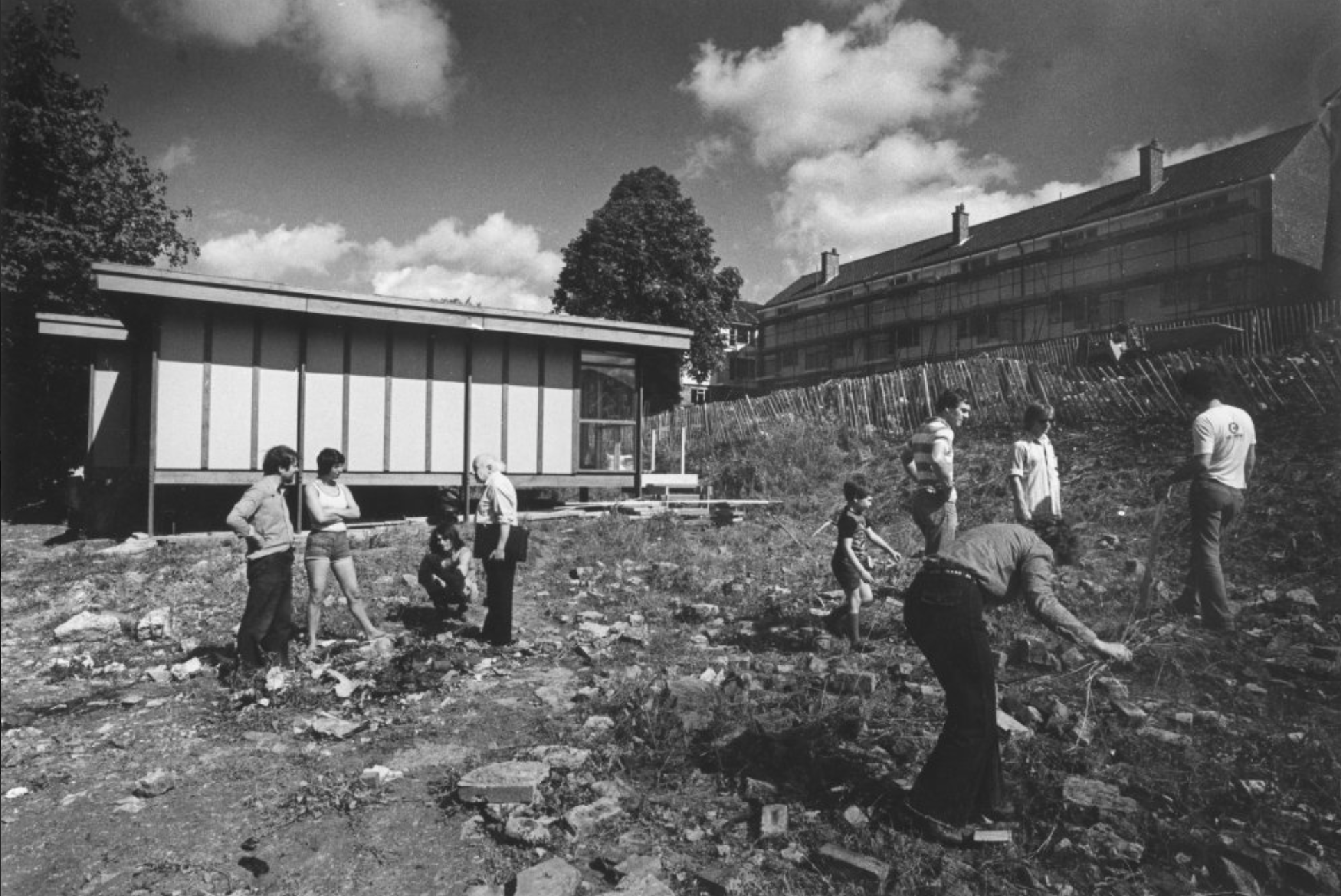

1. Walter Segal meets self-builders on-site at Segal Close, Honor Oak Park, Lewisham, London

Deconstruction of the triangular hierarchy

In the second phase of the settlement project, residents’ involvement had already begun at the design stage. With a standardised outline of the building and a fixed core, the interior layouts could be personalised and adapted to one’s needs. “(Inhabitants) were encouraged to conjure their interior layouts. In this case, architects supported and assisted the client, who was equally involved in both - project design and building construction,” 2 says architect Hugh Strange.

The construction began in 1979, with entire families involved in building processes while maintaining their daily jobs. People shared experiences and supported each other, as their knowledge came from this exchange rather than from understanding architectural plans or having any expertise. H. Strange recalls, “Self-builders, to a large extent, learned how to build from each other on the site rather than from the drawings given by the architects.” 3 On top of that, the community was given the opportunity to attend a series of workshops, preparing them for this unique project.

![]()

2. Getting closer now.

With this open approach to a construction site - a space mainly occupied by specialists - inhabitants had the chance to not only plan their house on paper but also bring it to life. Segal's earlier concepts and achievements made this possible. Based on that and and further simplifications of the building process, the construction site opened up to community interactions.

![]()

3. Getting closer now.

With this open approach to a construction site - a space mainly occupied by specialists - inhabitants had the chance to not only plan their house on paper but also bring it to life. Segal's earlier concepts and achievements made this possible. Based on that and and further simplifications of the building process, the construction site opened up to community interactions.

“The most impressive thing about Walter Segal was (…) that he moved his practice to a position which blurs the distinction between architect, builder and client. They aren’t at the three corners of a triangular relationship, but are all mixed up in the middle of the adventure of building” 4 Colin Ward, AJ, 1985

Reconstruction of non-hierarchical environment

The exchange of experience between inhabitants intertwined with the practical need for assistance and help. While working on their houses, people always found a helping hand from their future neighbours. Being a relatively small community and sharing the same struggles and challenges, a mutual understanding and sense of responsibility emerged. “There was a lot of peer-group support… We’d be working on our individual homes, but when it was time to raise the main frame of the house, the whole group would stop what they were doing and come and help.” 5, say Dave Dayes and his partner Barabara Hicks, members of the community.

This initiative not only built physical matter and social bonds but also helped individuals gain a sense of agency and confidence. From deciding on the spatial layout, learning new skills, and being able to apply them during construction to finally building their own houses - everyone could find fulfilment and a sense of belonging at every step of this experience. “It gives you that supreme confidence to do anything.” 6 said one of the community members while reflecting on the building process. Independence and freedom - the principles that Walter Segal believed in architectural practice - resonate fully through the physical and social outcomes of Walter’s Way and Segal Close.

![]()

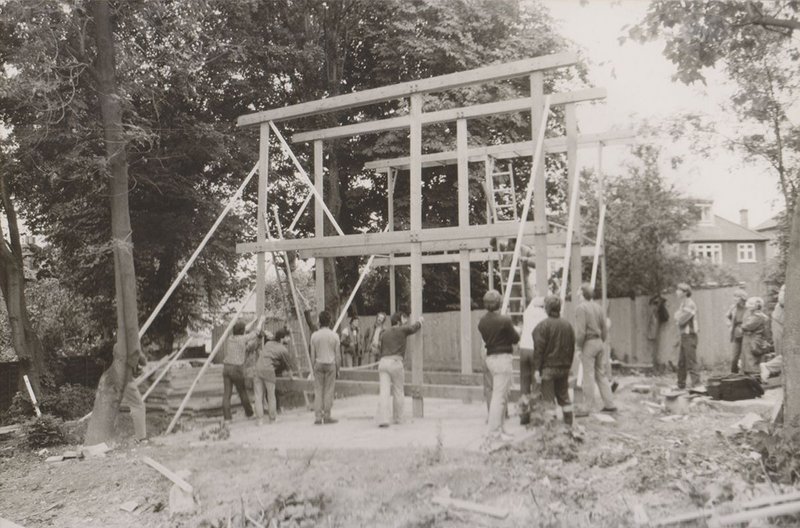

4. Erecting the structure.

The actual construction

In addition to the social benefits of Walter’s Method, these two projects pioneered sustainability and localism. Materials needed for completing the house were affordable and available from local sources, such as sawmills. The construction system was modular; measurements were based on the standards of available beam or board sizes. To maintain modularity, Segal provided a certain margin of error in the system in case of changes in dimensions, thus allowing the system's practicality to continue, regardless of market changes. “Segal’s pioneering projects in the 1970s and 80s, which were clearly several decades ahead of their time with regards to sustainability and open-source design.”7, says Pamela Buxton in her review.

The case of Walter Segal’s determination and consistency materialised, providing an example of translating architectural values into a vibrant community. By applying his concepts, Segal opened the inaccessible space of the construction site to people, thus allowing support, collaboration and democracy to take place.

From this perspective, dedication and willingness in the building process can become more than labour and the materialisation of a project. Building together allows interactions and relations to emerge, creating bonds that encourage a sense of co-responsibility, agency, and community. |

07/2024, Vienna

Passing the fences of urban construction sites, the mystery builds up. Often enclosed for safety measures, building sites remain inaccessible for those outside the triangular hierarchy- architects, investors and construction companies. With more significant projects, the mystery of what happens behind the fence is mimicked by colourful renders with cheerful people placed around newly built or renovated spaces. While some people try to peek through the gaps between the fence spans, others jump up or bend over the covers, the most pass by impassively.

A construction site is defined as “an area of land where something is being built” 1 and is possibly described by several other characteristics, such as the involvement of different professionals like architects, engineers, construction managers, and labourers. It can, therefore, be said that the construction site is a place of human interaction, a temporarily demarcated space within which relationships are formed. In particular, relationships between industry professionals.

And what if de-professionalised, one were to look at the construction sites simply as places of human interactions? If, with the guidance of professionals, the community was involved in the building processes?

In this way, the construction site was to be seen as a place for creating and enhancing neighbourhood interactions and social responsibility. Self-build projects can serve as platforms for raising awareness and a sense of belonging, as well as building and forming social bonds. This perspective allows for a deeper understanding of the social dynamics and collaborative processes forming at construction sites.

A great example of such an attempt occurred in the 1980s in London. Walter’s Way and Segal Close are two settlements based on a self-build housing scheme. The concept for this initiative was born out of the architectural reflections and personal developments of Berlin-born architect Walter Segal. From the beginning of his career, Segal was concerned with questions about ‘empowerment, collaboration, and democratic design’. With these thoughts in mind, he delved into architecture until he sparked the self-build revolution.

The actual translation of his ideas into physical matter occurred in 1963. During the construction of his own house, Segal erected a temporary structure for his family to live in. All the methods used in that project eventually became the main principles of Walter’s Way and Segal Close. The house was based on a modular system, with easily accessible building components, and took just two weeks to build. In the 1970s, London was grappling with a housing crisis, and the city’s council embraced Segal’s Method openly and enthusiastically. Eventually, the concept of the main structure was simplified so that people without professional experience could build their own houses.

1. Walter Segal meets self-builders on-site at Segal Close, Honor Oak Park, Lewisham, London

Deconstruction of the triangular hierarchy

In the second phase of the settlement project, residents’ involvement had already begun at the design stage. With a standardised outline of the building and a fixed core, the interior layouts could be personalised and adapted to one’s needs. “(Inhabitants) were encouraged to conjure their interior layouts. In this case, architects supported and assisted the client, who was equally involved in both - project design and building construction,” 2 says architect Hugh Strange.

The construction began in 1979, with entire families involved in building processes while maintaining their daily jobs. People shared experiences and supported each other, as their knowledge came from this exchange rather than from understanding architectural plans or having any expertise. H. Strange recalls, “Self-builders, to a large extent, learned how to build from each other on the site rather than from the drawings given by the architects.” 3 On top of that, the community was given the opportunity to attend a series of workshops, preparing them for this unique project.

2. Getting closer now.

With this open approach to a construction site - a space mainly occupied by specialists - inhabitants had the chance to not only plan their house on paper but also bring it to life. Segal's earlier concepts and achievements made this possible. Based on that and and further simplifications of the building process, the construction site opened up to community interactions.

3. Getting closer now.

With this open approach to a construction site - a space mainly occupied by specialists - inhabitants had the chance to not only plan their house on paper but also bring it to life. Segal's earlier concepts and achievements made this possible. Based on that and and further simplifications of the building process, the construction site opened up to community interactions.

“The most impressive thing about Walter Segal was (…) that he moved his practice to a position which blurs the distinction between architect, builder and client. They aren’t at the three corners of a triangular relationship, but are all mixed up in the middle of the adventure of building” 4 Colin Ward, AJ, 1985

Reconstruction of non-hierarchical environment

The exchange of experience between inhabitants intertwined with the practical need for assistance and help. While working on their houses, people always found a helping hand from their future neighbours. Being a relatively small community and sharing the same struggles and challenges, a mutual understanding and sense of responsibility emerged. “There was a lot of peer-group support… We’d be working on our individual homes, but when it was time to raise the main frame of the house, the whole group would stop what they were doing and come and help.” 5, say Dave Dayes and his partner Barabara Hicks, members of the community.

This initiative not only built physical matter and social bonds but also helped individuals gain a sense of agency and confidence. From deciding on the spatial layout, learning new skills, and being able to apply them during construction to finally building their own houses - everyone could find fulfilment and a sense of belonging at every step of this experience. “It gives you that supreme confidence to do anything.” 6 said one of the community members while reflecting on the building process. Independence and freedom - the principles that Walter Segal believed in architectural practice - resonate fully through the physical and social outcomes of Walter’s Way and Segal Close.

4. Erecting the structure.

The actual construction

In addition to the social benefits of Walter’s Method, these two projects pioneered sustainability and localism. Materials needed for completing the house were affordable and available from local sources, such as sawmills. The construction system was modular; measurements were based on the standards of available beam or board sizes. To maintain modularity, Segal provided a certain margin of error in the system in case of changes in dimensions, thus allowing the system's practicality to continue, regardless of market changes. “Segal’s pioneering projects in the 1970s and 80s, which were clearly several decades ahead of their time with regards to sustainability and open-source design.”7, says Pamela Buxton in her review.

The case of Walter Segal’s determination and consistency materialised, providing an example of translating architectural values into a vibrant community. By applying his concepts, Segal opened the inaccessible space of the construction site to people, thus allowing support, collaboration and democracy to take place.

From this perspective, dedication and willingness in the building process can become more than labour and the materialisation of a project. Building together allows interactions and relations to emerge, creating bonds that encourage a sense of co-responsibility, agency, and community. |

References:

- Oxford Dictionary: https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/english/construction-site

- Hugh Strange: Walter Segal and the Rigorous Simplification of Building Process, lecture at Architecture Foundation: https://youtu.be/jfAJSPj0cX4?si=vrTzsP8-BmVCaV-J

- Hugh Strange: Walter Segal and the Rigorous Simplification of Building Process, lecture at Architecture Foundation: https://youtu.be/jfAJSPj0cX4?si=vrTzsP8-BmVCaV-J

- Colin Ward, AJ, 1985

- the commentary originally published in Guardian, https://www.themodernhouse.com/journal/architect-walter-segal-self-build/

- Walter’s Way, Lewisham, video by at Architecture Foundation, https://youtu.be/0JbqJNAUOR8?si=1AnLBfzMj3gieE3w

- https://www.ribaj.com/culture/the-segal-show

Sources:

- https://www.themodernhouse.com/journal/architect-walter-segal-self-build/

- https://www.ribaj.com/culture/the-segal-show

- https://charlieluxtondesign.com/walter-segal-exhibition/

- https://www.themodernhouse.com/directory-of-architects-and-designers/walter-segal/

Pictures:

- Photographer: Sayer Phil, 1988, https://www.ribapix.com/walter-segal-meets-self-builders-on-site-at-segal-close-honor-oak-park-lewisham-london_riba34555

- Getting closer now. Credit: Martin Charles, courtesy Jon Broome, https://www.ribaj.com/culture/the-segal-show

- Getting closer now. Credit: Martin Charles, courtesy Jon Broome, https://www.ribaj.com/culture/the-segal-show

- Erecting the structure. Credit: Image Courtesy Jon Broome, https://www.ribaj.com/culture/the-segal-show